Playing “Dukes of Hazzard” for real

Playing “Dukes of Hazzard” for real

In the cartoon world of “Dukes of Hazzard”, Boss Hogg ran Hazzard County with a comically pudgy iron hand. The County was his fiefdom, and Sherriff Roscoe P. Coltrane his goofy but strongarm enforcer. The law was a fig leaf to be worn (or not) as it suited the Boss’s greed. Hilarity ensued.

In the cartoon world of “Dukes of Hazzard”, Boss Hogg ran Hazzard County with a comically pudgy iron hand. The County was his fiefdom, and Sherriff Roscoe P. Coltrane his goofy but strongarm enforcer. The law was a fig leaf to be worn (or not) as it suited the Boss’s greed. Hilarity ensued.

In the real world, towns, cities, states, and even the Feds have a powerful tool to create their own little extortionary fiefdoms in a previously free country… Civil Asset Forfeiture. This charming idea takes advantage of a “loophole” in the basic concepts of justice going back to the Magna Carta. When the State takes action against YOU, YOU have rights and the STATE must prove you’re guilty before your property can be seized. That’s criminal law. Civil Asset Forfeiture is based in civil law, so the State goes after your PROPERTY instead of you, shifting the burden of proof to YOU because your property has no rights. Roscoe gets

complete authority to seize your property based on such criminally suspicious behavior as “having an air freshener hanging from your mirror”. YOU have to pay for an attorney to PROVE your property wasn’t involved in illegal activity, and the person deciding if you’ve proved your case is Boss Hogg. Hilarity does NOT ensue.

The Boss’s fig leaf for this extortion is, of course, the “war on drugs.” Officials call Civil Asset Forfeiture a powerful tool to use against drug kingpins but their actions belie those motivations. One example is Volusia County, Florida, where interstate highways serve as main corridors for the drug trade. Most drugs on this road flow north (into the country) while most cash flows south (out of the country). However, most Volusia County seizures involve southbound rather than northbound travelers, suggesting that the drug cops are targeting fat bags of cash rather than dangerous criminals. Far from being the prime motivator of the stops, no criminal charges were even filed in over 75% of the County’s seizure cases.

The Boss’s fig leaf for this extortion is, of course, the “war on drugs.” Officials call Civil Asset Forfeiture a powerful tool to use against drug kingpins but their actions belie those motivations. One example is Volusia County, Florida, where interstate highways serve as main corridors for the drug trade. Most drugs on this road flow north (into the country) while most cash flows south (out of the country). However, most Volusia County seizures involve southbound rather than northbound travelers, suggesting that the drug cops are targeting fat bags of cash rather than dangerous criminals. Far from being the prime motivator of the stops, no criminal charges were even filed in over 75% of the County’s seizure cases.

To give you an idea of how big this scam is, forfeitures from 1989-2010 totaled over $12.6 BILLION. The total was $4.2 billion just in 2012, up from $1.7 billion in in 2011, and the Feds are expecting nearly $5 billion when 2013’s totals are in.

It’s not just property at risk. Teneha, Texas, is a poster child for Civil Asset Forfeiture abuse. A couple and their children were pulled over for driving in the left lane without passing. A search (seriously, a search!) uncovered a pipe but no drugs. Into jail anyway, where they learned they “fit the profile” of drug couriers… they were driving from Houston, “a known point for distribution of illegal narcotics” to Linden, “a known place to receive illegal narcotics”. The children in their car were dismissed as decoys but they still played a role in the story… the couple were offered the choice of facing charges and handing their kids over to foster care, or sign over their $6,037 and be on their way. They paid.

Most people hearing about Civil Asset Forfeiture think it can’t possibly be happening here, and even those who know about it rarely realize the scope. To get your forehead veins popping this month we bring you a buffet of stories on the subject- you’ll find case examples, legal reasoning, videos, even a website for cops who want to make it big in the Civil Asset Forfeiture

business. When you know the story you’ll agree… it’s funny when Boss and Roscoe do it, but the reality will make you Furious.

Stop and Seize, Investigative report in The Washington Post; September 2014

After the terror attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, the government called on police to become the eyes and ears of homeland security on America’s highways. Local officers, county deputies and state troopers were encouraged to act more aggressively in searching for suspicious people, drugs and other contraband. The departments of Homeland Security and Justice spent millions on police training. The effort succeeded, but it had an impact that has been largely hidden from public view: the spread of an aggressive brand of policing that has spurred the seizure of hundreds of millions of dollars in cash from motorists and others not charged with crimes, a Washington Post investigation found. Thousands of people have been forced to fight legal battles that can last more than a year to get their money back. Behind the rise in seizures is a little-known cottage industry of private police-training firms that teach the techniques of “highway interdiction” to departments across the country.

After the terror attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, the government called on police to become the eyes and ears of homeland security on America’s highways. Local officers, county deputies and state troopers were encouraged to act more aggressively in searching for suspicious people, drugs and other contraband. The departments of Homeland Security and Justice spent millions on police training. The effort succeeded, but it had an impact that has been largely hidden from public view: the spread of an aggressive brand of policing that has spurred the seizure of hundreds of millions of dollars in cash from motorists and others not charged with crimes, a Washington Post investigation found. Thousands of people have been forced to fight legal battles that can last more than a year to get their money back. Behind the rise in seizures is a little-known cottage industry of private police-training firms that teach the techniques of “highway interdiction” to departments across the country.

Civil Asses Forfeiture In-Depth

A 123-page PDF report from the Institute for Justice including state-by-state breakdown.

Here are four of the most disturbing facts from the Post’s investigation:

- State and local authorities kept more than $1.7 billion of the $2.5 billion in cash seizures made since 2001.

- Only one sixth of the seizures were challenged in court, thanks in part to the exorbitant costs of taking legal action against the government.

- The program is a critical source of revenue for hundreds of state and local departments. Since 2008, 298 departments and 210 task forces have seized what amounts to 20% or more of their annual budgets.

- Despite the fact that law enforcement officials in states like Kansas refuse to participate in the “highway interdiction” program because they worry it may not be legal, Justice and Homeland Security officials continue to use it.

Easy Money: Civil Asset Forfeiture Abuse by Police, ACLU Blog of Rights; February 2010

On November 18, 2009, Shukree Simmons, who is African-American, was driving with his business partner on the highway from Macon, Georgia, back to Atlanta after selling his cherished Chevy Silverado truck to a restaurant owner in Macon for $3,700 of sorely needed funds. As Mr. Simmons passed through Lamar County, he was pulled over by two patrol officers who stated no reason for the stop, but instead asked Mr. Simmons numerous questions about where he was going and where he had been, and even separated him from his business partner for extended questioning. The officers searched both people and the car, finding no evidence of any illegal activity. A drug dog sniffed the car and did not indicate the presence of any trace of drugs. Notwithstanding the total lack of evidence of criminal activity and Mr. Simmons’s explanation that he was carrying money from selling his truck, the officers confiscated the $3,700 on the suspicion that the funds were derived from illegal activity, pursuant to their authority under Georgia’s civil asset forfeiture law. Despite the fact that Mr. Simmons mailed his bill of sale and title for the truck to the officer, he was told over the phone that he would need to file a legal claim to get his money back…

Like what you’re reading? Does a career in justice-flavored thuggery sound good to you?

There’s a website that’s ready to help you down the road…

Cops Use Traffic Stops To Seize Millions From Drivers Never Charged With A Crime, Nick Sibilla in Forbes; March 2014

A deputy for the Humboldt County’s Sheriff Office in rural Nevada has been accused of confiscating over $60,000 from drivers who were never charged with a crime. These cash seizures are now the subject of two federal lawsuits and are the latest to spotlight a little-known police practice called civil forfeiture. Civil forfeiture allows law enforcement to seize property (including cash and cars) without having to prove the owners are guilty. Last September, Tan Nguyen was pulled over for driving three miles over the speed limit, according to a suit he filed. Deputy Lee Dove asked to search the car but Nguyen said he declined. Dove claimed he smelled marijuana but couldn’t find any drugs. The deputy then searched the car and found a briefcase containing $50,000 in cash and cashier’s checks, which he promptly seized. According to the Associated Press, Nguyen said he won that cash at a casino.

Sourovelis v. City of Philadelphia- Fighting the Philadelphia Forfeiture Machine, Institute for Justice

Philadelphia’s automated, machine-like forfeiture scheme is unprecedented in size. From 2002 to 2012, Philadelphia took in over $64 million in forfeiture funds—or almost $6 million per year. In 2011 alone, the city’s prosecutors filed 6,560 forfeiture petitions to take cash, cars, homes and other property. The Philadelphia District Attorney’s office used over $25 million of that $64 million to pay salaries, including the salaries of the very prosecutors who brought the forfeiture actions. This is almost twice as much as what all other Pennsylvania counties spent on salaries combined…

Highway Robbery: Tennessee Police Are Seizing Cash From Out-of-State Visitors In Policy Called “Policing For Profit”, Jonathan Turley; May 2012

The Daily Show- Highway-Robbing Highway Patrolmen Unsurprisingly, Jon Stewart has a very funny take on a very serious problem.

Bates said that he was right to take the money because “he couldn’t prove it was legitimate.” That of course flips the normal presumption under criminal law, but it is an example of how police powers have increased in this country.

To made matters even more authoritarian, Tennessee law allows a judge to sign off on the seizure in an ex parte proceeding. Reby was never informed of the hearing. Only the officer’s account is considered at such hearings.

While Reby insists that he offered to show proof on his computer as to the source of the money, the offer was not reported to the court. Bates simply stated “common people do not carry this much U.S. currency.” He noted later that “a thousand-dollar bundle could approximately buy two ounces of cocaine.” Of course, ten dollars can buy drugs as well as a thousand dollars can buy a jet ski.

Bates also said Reby had a criminal history despite the fact that it was 20 years ago and did not result in any conviction. He also said the money was hidden in the car despite the fact the Reby consented to the search and told the officer about the bag (and gave the bag to the officer).

Highway Robbery- Police have incentives to commit legalized highway robbery., Bruce Benson in The Freeman; July 1993

In 1863, Henry Plummer was sheriff of the gold camp at Bannock, Montana. He also organized a gang of about 100 “road agents” who stole from miners and travelers; his deputies were horse thieves, stagecoach robbers, and murderers. Citizens could do something about highway robbery by their sheriff in 1863, however. Since Plummer was breaking the law, a vigilante committee arrested, tried, and hanged him in short order, along with 21 members of his gang, banished several others from the area, and frightened off most of the rest.

Today, the sheriff of Volusia County, Florida, also leads an organized band of “road agents” who confiscate cash from travelers on Interstate 95. His road agents are called the “drug squad” and they have seized an average of $5,000 per day from motorists during the 41 months preceding June 1992 and over $8 million dollars since 1989. But Floridians cannot do anything about this highway robbery, because it is perfectly legal under the state’s asset seizure law.

Such highway robbery is being “justified” as part of a “war on drugs.” Actually, however, most Volusia County seizures involve southbound rather than northbound travelers, suggesting that the drug squad is more interested in seizing money than in stopping the flow of drugs. In fact, no criminal charges were filed in over 75 percent of the County’s seizure cases. But more significantly, a substantial amount of money has been stolen from innocent victims. In order to get their money back, these people must undertake an expensive civil trial to prove their innocence, something most decide they cannot afford to do…

ACLU on Civil Asset Forfeiture,

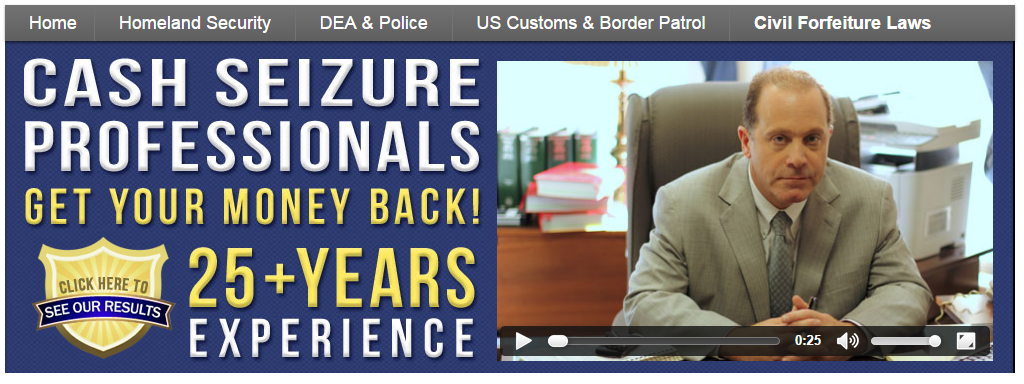

Had your stuff taken by The Man? This man can help… Geoffrey G. Nathan, Cash & Money Seizure Legal Specialists

Every year, federal and state law enforcement agents seize millions of dollars from civilians during traffic stops, simply by asserting that they believe the money is connected to some illegal activity and without ever pursuing criminal charges. Under federal law and the laws of most states, they are entitled to keep most (and sometimes all) of the money and property they seize. In many jurisdictions, the money can go to pay for salaries, advanced equipment and other perks. When salaries and perks are on the line, officers have a strong incentive to increase the seizures, as evidenced by an increase in the regularity and size of such seizures in recent years. Asset forfeiture practices often go hand-in-hand with racial profiling and disproportionately impact low-income African-American or Hispanic people who the police decide look suspicious and for whom the arcane process of trying to get one’s property back is an expensive challenge. ACLU believes that such routine “civil asset forfeiture” puts our civil liberties and property rights under assault, and calls for reform of state and federal civil asset forfeiture laws.

Taken, Sarah Stillman in The New Yorker; August 2013

The county’s district attorney, a fifty-seven-year-old woman with feathered Charlie’s Angels hair named Lynda K. Russell, arrived an hour later. Russell, who moonlighted locally as a country singer, told Henderson and Boatright that they had two options. They could face felony charges for “money laundering” and “child endangerment,” in which case they would go to jail and their children would be handed over to foster care. Or they could sign over their cash to the city of Tenaha, and get back on the road. “No criminal charges shall be filed,” a waiver she drafted read, “and our children shall not be turned over to CPS,” or Child Protective Services. “Where are we?” Boatright remembers thinking. “Is this some kind of foreign country, where they’re selling people’s kids off?” Holding her sixteen-month-old on her hip, she broke down in tears…

PLUS TWO GOOD NEWS UPDATEs! East Texas DA faces civil rights lawsuit without government help, and Settlement Means No More Highway Robbery in Tenaha, Texas

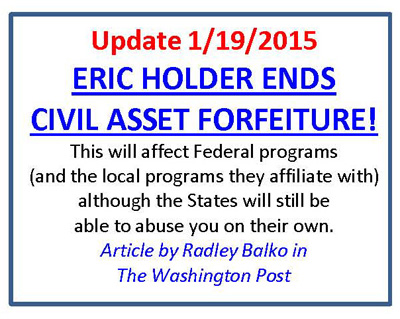

Minnesota Now Requires A Criminal Conviction Before People Can Lose Their Property To Forfeiture, Nick Sibilla in Forbes; May 2014

In a big win for property rights and due process, Minnesota Gov. Mark Dayton signed a bill yesterday to curb an abusive—and little known—police practice called civil forfeiture. Unlike criminal forfeiture, under civil forfeiture someone does not have to be convicted of a crime, or even charged with one, to permanently lose his or her cash, car or home.

The newly signed legislation, SF 874, corrects that injustice. Now the government can only take property if it obtains a criminal conviction or its equivalent, like if a property owner pleads guilty to a crime or becomes an informant. The bill also shifts the burden of proof onto the government, where it rightfully belongs. Previously, if owners wanted to get their property back, they had to prove their property was not the instrument or proceeds of the charged drug crime. In other words, owners had to prove a negative in civil court. Being acquitted of the drug charge in criminal court did not matter to the forfeiture case in civil court.

Stopping The Abuse Of Civil Forfeiture, Michigan Congressman Tim Walberg in The Washington Post; September 2014

Imagine you are driving down the highway on your way to buy a car. You spent months researching years, makes and models, and you finally found somebody who was selling the exact ride you were looking for at a reasonable price. Suddenly, police pull you over for allegedly going 37 mph in a 35 mph zone. Upon discovering the $8,500 in cash you have on hand, the officers take you to jail and threaten to charge you with money laundering unless you turn over the money. Frightened, you give it to them.

This may sound like something out of a Hollywood movie, but it’s a true story, and incidents like it happen all too often across the country because of our civil forfeiture laws. Fortunately, the victim in the above story, Roderick Daniels, had his property returned by officials due to media attention and legal pressure. But the power to take property without due process continues to be abused by local, state and federal law enforcement officials. In my state of Michigan, grocery store owner Terry Dehko had his bank account seized by the IRS because it suspected him of being a money launderer. Dehko would make cash deposits in the bank across the street every night to reduce the threat of robbery and because of coverage limits on his store’s insurance policy. Charges were never filed, but Dehko had to fight in court to prove that his money was not being used in a criminal enterprise.

Civil asset forfeiture abuse takes away right to be presumed innocent, Ken Braun on MLive; January 2014

It’s easy to understand why police chiefs don’t receive hefty commissions for traffic tickets. If they did, then traffic stops for trivially small speeding violations would multiply like weeds, and eagle-eyed deputies would be on the lookout to pounce on every technical failure to signal a turn. Changing the law enforcement incentive from protecting public safety to bureaucratic profit would obliterate the basic presumption of innocence at the heart of our legal system. The police would be looking at drivers as marks to be fleeced, rather than citizens whose rights must be protected and respected…

The continuing outrage that is civil asset forfeiture, Radley Balko in The Washington Post; July 2014

The motorist advocacy site TheNewspaper.com has the story of 64-year-old Laura Dutton. Estelline, Tex., police officer Jason Fry was manning a speed trap (a spot where the speed limit suddenly drops) when he pulled Dutton over for driving 61 mph just into the 50 mph zone. Here’s what happened next:

Officer Fry said he “smelled marijuana” so a drug dog was called in, and when the K-9 arrived thirty minutes later, it alerted. Dutton had no drugs, but she was carrying $31,000 in cash, the bills wrapped up as they had come fresh from the bank. She had recently earned the sum from the sale of 12.9 acres of land in Van Zandt County. Despite the explanation, Officer Fry grabbed the cash and arrested Dutton, who had no criminal record of any kind, for “money laundering.” Officer Fry handed the money over to Estelline City Manager Richard Ferguson.

Two months after the money had been taken from her, the charges were finally dropped and $29,640 returned to Dutton. In addition to the $1400 stolen from her by the city, Dutton was out $1050 in fees she had to pay to get out of jail the day after her arrest. She was never reimbursed for the travel expenses she incurred to get her money back.

Dutton filed a complaint. The city didn’t bother to investigate. So she sued. The city claimed in discovery that all video related to Dutton’s arrest had been destroyed. (Sound familiar?) Fortunately, a Texas judge didn’t buy into any of this. Faced with the possibility of a jury trial in front of a sympathetic plaintiff, the city settled for $77,500. It seems unlikely that the settlement will be enough to end the harassment and fishing expeditions. Consider that Estelline police need only find three more Laura Duttons who don’t sue to more than recoup the city’s losses. Here’s the kicker: The Amarillo Globe-News reports that 89 percent of Estelline’s 2012 gross revenue came from asset forfeiture.

EDITORIAL: Putting a stop to civil asset-forfeiture abuse, Washington Post editorial; May, 2014

When cops can help themselves to cash, cars, boats and houses of citizens who have never been charged with a crime, the system is badly broken. Minnesota has become one of the handful of states to do something to fix it.

Under the surreal doctrine of civil forfeiture, law enforcement agents can set aside constitutional protections and simply seize property under the assertion that the property is probably related to some kind of criminal activity. This is often an irresistible temptation, and the state gets away with it by laying charges against inanimate objects, which have no rights, instead of people, who do. This reverses the presumption of innocence, allowing money, cars, and even the occasional motel to become the constable’s property without a judge finding the actual owner guilty of anything. It’s up to the owner to prove the cops wrong, and if there’s any doubt, the government wins. The system is rigged to favor those who are corrupt.

Policing for Profit? Lawmakers, advocates raise alarm at growing gov’t power to seize property, Barnini Chakraborty on Fox News Politics; May 2014

Motel owner Russell Caswell wasn’t expecting to find himself at the center of a national controversy when FBI agents came knocking on his door. They said they wanted his Tewksbury, Mass., business – and the land it was on – because they suspected it was a hotbed for drug-dealing and prostitution. The agents, who were working with state and local authorities, told a disbelieving Caswell they had the right to take the property, valued at as much as $1.5 million, through a legal process known as civil forfeiture. Caswell, 70, fought back, and the case turned into one of the nation’s most contentious civil forfeiture fights ever – and one that legal experts say sheds light on a little-known practice that, when abused, is tantamount to policing for profit.

Reining in Forfeiture: Common Sense Reform in the War on Drugs, Kyla Dunn for Frontline

Last year, almost a billion dollars worth of cash, cars, boats, real estate, and other property was forfeited to the federal government–most of it labeled as drug-related. And while much of this property was taken from bona fide criminals, critics of the nation’s forfeiture laws say that too many innocent people have fallen through the cracks in a system that, until recently, has been far too heavily slanted in the government’s favor. Retreat is rare in our nation’s drug war–which makes recent roll-backs to the forfeiture laws all the more remarkable. In their scramble not to appear “soft on crime,” lawmakers normally seem able only to get tougher, even amidst widespread agreement that a policy is flawed. But on August 23rd, 2000, after a difficult seven-year campaign by Republican Congressman Henry Hyde from Illinois, the Civil Asset Forfeiture Reform Act finally went into effect–making it more difficult for the federal government to seize property without evidence of wrongdoing. It took a remarkable coalition of conservative and liberal lawmakers, to change a law that everyone from the American Civil Liberties Union to the National Rifle Association has recognized as flawed. And while the reforms come too late to help Rudy Ramirez, they will help to make cases like his rarer.

Civil Asset Forfeiture: The Biggest Little Racket in Nevada, Jason Snead and Andrew Kloster on The Daily Signal; April 2014

It was highway robbery, but they called it civil asset forfeiture. On the last day of his 2,400-mile drive to start a new life on the West Coast, Matt Lee found himself on the side of the road, his belongings combed through, and drug dogs sniffing his car. Why? Because Lee made the mistake of telling Humboldt County, Nevada, sheriff’s deputy Lee Dove that he had $2,400 in cash. Lee chronicled what happened in the Silver Pinyon Journal, and it reads like a dark, twisted version of the cop-comedy Super Troopers. The deputy claimed that he was interested only in people traveling with more than $10,000. (After all, Lee was assured, it is not illegal to have cash.) Lulled into a false sense of security, Lee told the deputy about the money he had stowed in his trunk for the move, a gift from his father to help him get started with the next chapter of his life.

Deputy Dove emptied the contents of Lee’s car onto the side of the road, sliced open his bags, and questioned his “cover story” that he was off to start fresh in California. The deputy found no evidence of drugs or illegal activity, but in the world of civil asset forfeiture, you don’t need to in order to seize someone’s property. The deputy wrote Lee a receipt for his money, then seized it on the pretense that he suspected Lee of traveling cross-country to buy illegal narcotics…